Perpetuating Scientific Fraud Through Storytelling | Mask Theatre

Who doesn't love a good story?

What if I told you jet planes don’t require as much fuel as we’re led to believe because their engines are incredible feats of engineering and using “fuel cost” as an excuse for huge surges in ticket price is dishonest?

What if I told you burning jet fuel doesn’t make fireproofed steel skyscrapers collapse neatly into their own footprint?

What if I told you amateur pilots couldn’t (and wouldn’t attempt to) pull off dramatic banking maneuvers at high speeds and low altitudes in jet planes when attempting to hit buildings in an elaborate terror plot?

What if I told you no planes crashed on 9/11/01?

Would you think everything above is correct? Incorrect? A mix of truth and fiction? Unsure? Does this pique your interest? Offend you? Make you think I’m insensitive? Crazy? Unqualified? A silly goose? Clever? Awake? Will this send you down a rabbit hole? Will this end your readership here? And why?

Storytelling shapes our perception of truth and we all consume stories differently based on a wide variety of factors unique to each of us.

The 9/11 Commission Report gave us the “official” story concerning the events of September 11th. For many, that’s the truth and anyone who questions it too much is just selfishly speculating for their own personal agenda or is a conspiracy theorist whacko. For others, there are certainly some missing pieces…but thank goodness we took out that Osama Bin Laden! Some people still have no clue what to make of that day. The rest dismiss the story outright and, to some degree, theorize about what may or may not have happened.

Even with countless hours of storytelling, there remains a huge divide in what is thought to be true of that day. What remains one of the main drivers of that divide? Perceived scientific fraud.

Regardless of how many experts come forward, there are still great debates about the avionics of the (alleged) planes in question, the telecommunications of phones (allegedly) used on said planes, the aeronautics as the (alleged) amateur pilots navigated said planes, the chemistry of the (alleged) jet fuel and fire-proofed steel beams, the physics of building collapses, and the forensics of the result.

With more tools at our disposal than ever before—even without direct access to these crime scenes—it should be easy to determine fraud if it were there, right? Could it be that as our tools for investigation have become more sophisticated, so too have our tools for live storytelling? What if the tools that are being rolled out to the masses now are older than most people think? And what if our storytellers are not to be trusted?

With the content we consume, how do we know where fiction ends and programming the masses to believe in scientific impossibilities begins? Our eyes and ears often draw conclusions before our brain is able to do a careful analysis of the available evidence—but to what extent?

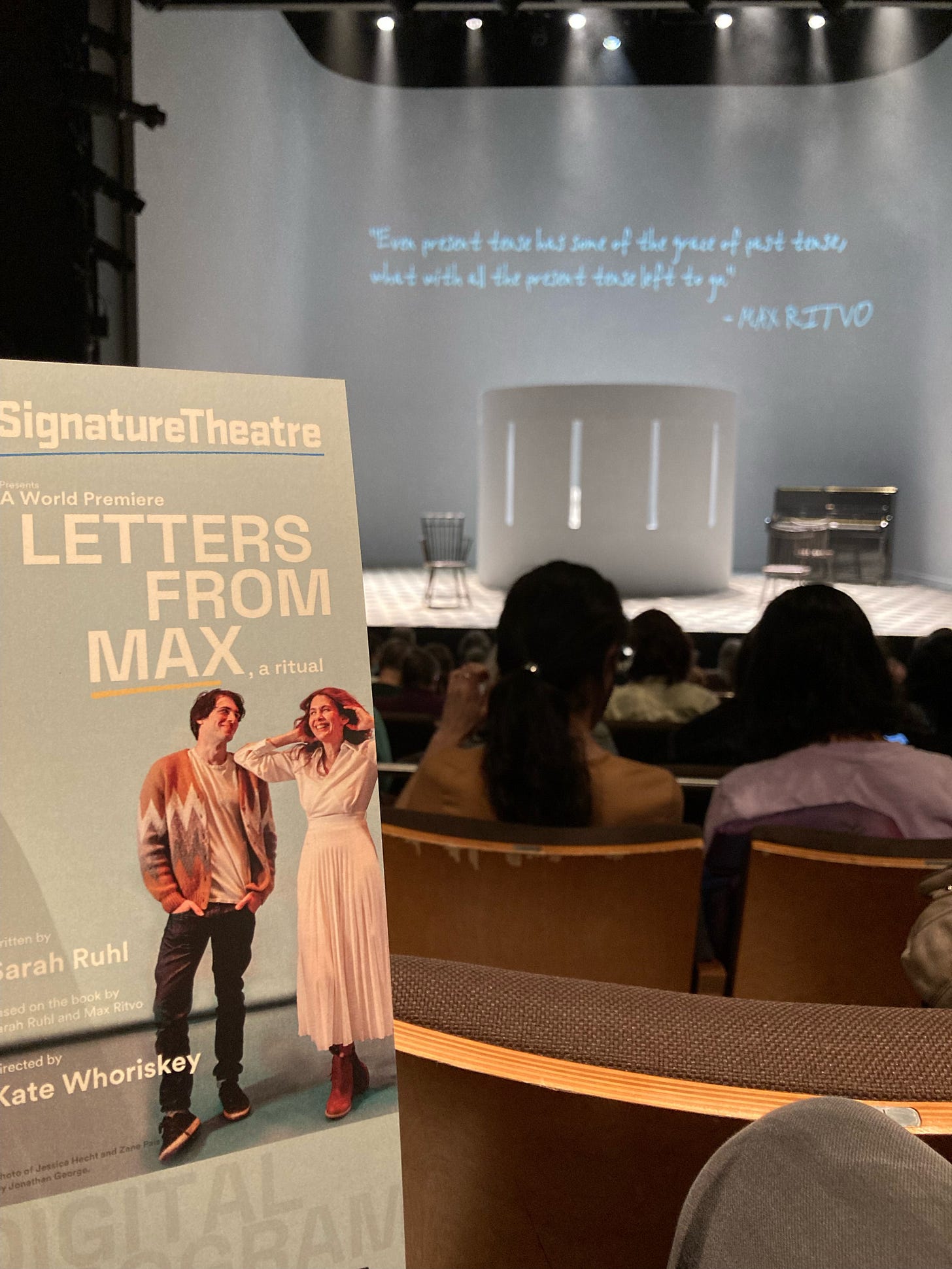

Sarah Ruhl is an award-winning writer best known for her plays, but she also wrote a memoir that touches on her high-risk twins pregnancy that led to a Bell’s palsy diagnosis. Currently running Off-Broadway in New York City at the Signature Theatre is Ruhl’s latest play, Letters From Max. Based on a book from 2018, the play includes poems, letters, and text messages passed between Ruhl and her student Max Ritvo who was actively battling cancer.

At the time of writing this, Signature Theatre has an optional mask policy for evening performances and “masked matinees.” While most of the general public has moved on from the use of these countermeasures, this venue still caters to a certain mostly-liberal groupthink that persists. The population most vocal about the right for women to choose what is best for their own bodies often fails to be consistent when it comes to COVID protocols. Now, it’s not that you don’t find plenty of hypocrisy elsewhere, it just seems to be rampant in this group right now.

If you were to attend a “masked matinee” of Letters From Max, it might go something like this:

You arrive to the Signature Theatre on 42nd Street a few minutes before 2pm and you’re directed upstairs. As you ascend the staircase, you take in the unique architecture and say to yourself, “Hot damn! Who designed this place? The next Frank Gehry?” You’d be wrong because it was actually Frank Gehry. You make your way over to a counter where you pick up your tickets from a masked person. You look around to see if everyone else is wearing a mask and you notice several other audience members are entering the theatre with naked faces. You do the same.

You find your place in the intimate theatre that seats less than 200. If you’re observant, you quickly notice no one is coughing or sneezing—just healthy people sharing a space together. You watch the first act. At intermission, you think to yourself that it’s a worthy topic to explore, but it might be a little more potent if it were a little less self-indulgent and performed in under 90 minutes with no intermission. You also think to yourself that asking a writer to trim down a script is like asking a dog not to sniff butts…good luck!

As you settle in for the second act, two masked employees enter the house and tell everyone they need to wear masks. After breathing the same air as both masked and unmasked guests for the past hour, you wonder why they are even bothering. You begin to think to yourself that maybe these people no longer have the ability to identify the fourth wall and maybe, at some point, the make-believe of theatre blended with their own reality. But how? Then, you start wondering if you’re living in a simulation, but you quickly direct your focus back to the stage for fear of feeling as ridiculous as the people handing out surgical masks to those not going into surgery look.

As the house lights begin to go down, a woman seated directly behind you mutters to her partner, “How much longer do we have to keep doing this? Forever? It’s not even that bad anymore.” Right on cue, a bespectacled young man with a dull personality sitting two seats down interjects with, “Actually, that’s not true.” He then regurgitates the latest New York Times opinion piece on why masks are still needed, how they’re going to protect children and he throws in something about AIDS for no reason as he demands a Faucian bargain from a fellow theatregoer. The actor playing Max comes on stage, silencing the college-educated, virtue signaling hypochondriac behind a KN95.

The second act begins with an immediate projection cue misfire. Along with a fresh mask on your face, the show suddenly vibes differently with you. As you watch Max deteriorate in a hospital gown, you start to feel like you’ve entered The Twilight Zone, The Truman Show, The Matrix. The heart-wrenching content makes people cry into their masks and you can’t help but think that people are more likely to get infections on their faces than in their lungs.

As the show comes to a close, you give the small-but-mighty cast the applause they rightfully earned. You take one glance over at the COVID monologist to see if he is about to start up again. Luckily for everyone, he doesn’t. You leave the theatre, rip off the mask, drop it in the nearest receptacle so it may one day join billions of friends somewhere across the river, and, as you casually stroll home, you begin to imagine the man who sat behind you giving a lecture on masks in landfills.

Reflecting on your experience, you wonder what it means for a creative team to explore a certain truth on stage while everyone around it perpetuates scientific fraud. Then, you think, had it not been for scientific fraud, would Max Ritvo still be alive today? Would this play even exist? Would there have been enough material for a book?

If art asks tough questions that science seeks to answer, what does it mean for art when there is so much scientific fraud?

An interesting and well written piece. A lot of the questions you pose need to be answered. But one thing I thoroughly disagree with is the insinuation there were no planes. I was working at American Airlines then. I retired from that company. During the 9/11 incident, I was a trained call taker on the 'Care Team' which was staffed to take calls from people inquiring about family/loved ones on any planes in incidents. I and many other employees actually knew someone who perished on one or the other of the planes. They were real people. This invalidates those people as being living beings and this is wrong. I have to speak out. That said, those towers were imploded, but they had to use the planes as a cover.

An interesting and well written piece. A lot of the questions you pose need to be answered. But one thing I thoroughly disagree with is the insinuation there were no planes. I was working at American Airlines then. I retired from that company. During the 9/11 incident, I was a trained call taker on the 'Care Team' which was staffed to take calls from people inquiring about family/loved ones on any planes in incidents. I and many other employees actually knew someone who perished on one or the other of the planes. They were real people. This invalidates those people as being living beings and this is wrong. I have to speak out. That said, those towers were imploded, but they had to use the planes as a cover.